RESEARCH PAPER

Assessment of the relationship between socio-demographic factors and intensity of perceived stress in a group of women hospitalized due to miscarriage

1

Katedra i Zakład Rozwoju Położnictwa

Wydział Nauk o Zdrowiu

Uniwersytet Medyczny w Lublinie

2

Warszawski Uniwersytet Medyczny, Wydział Lekarski

3

Katedra i Zakład Rozwoju Położnictwa Wydział Nauk o Zdrowiu Uniwersytet Medyczny w Lublinie, Polska

Corresponding author

Grażyna Jolanta Iwanowicz-Palus

Katedra i Zakład Rozwoju Położnictwa Wydział Nauk o Zdrowiu Uniwersytet Medyczny w Lublinie, ul. Staszica 4-6, 20-081, LUBLIN, Polska

Katedra i Zakład Rozwoju Położnictwa Wydział Nauk o Zdrowiu Uniwersytet Medyczny w Lublinie, ul. Staszica 4-6, 20-081, LUBLIN, Polska

Med Og Nauk Zdr. 2021;27(3):285-290

KEYWORDS

TOPICS

ABSTRACT

Introduction and objective:

In the literature, there are reports that miscarriage causes deterioration of the mental condition of women. The presented study made it possible to identify socio-demographic risk factors of an increased level of stress.

Objective:

The aim of the study was to determine the correlation between socio-demographic factors and the intensity of perceived stress inae group of women who were hospitalized due to miscarriage.

Material and methods:

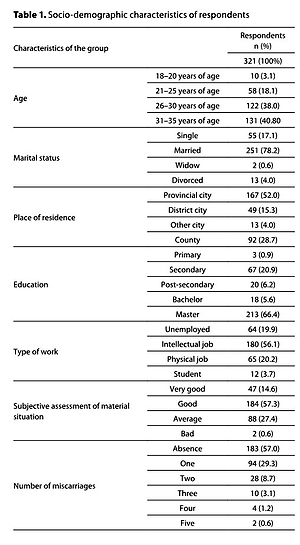

321 women aged 18–35 years hospitalized due to miscarriage took part in the study. The diagnostic survey method – the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10) and the author›s questionnaire were used.

Results:

Age determined the intensity of stress, which was greater in the group of women aged up to 25 years than in the group of older women. Place of residence, education and financial situation did not determine the level of subjectively perceived stress in the group of women hospitalized due to miscarriage. Income determined the intensity of stress, which was the highest in the group of women with an income of up to 700 PLN per person in the family. The occurrence of miscarriages did not determine the level of subjectively perceived stress.

Conclusions:

There is a correlation between sociodemographic factors and the intensity of perceived stress in the group of women who were hospitalized due to miscarriage. The assessment of the correlation between sociodemographic factors and the intensity of perceived stress made it possible to distinguish a group of women at increased risk of developing an increased level of stress, which includes women: up to 25 years of age and in the age range 31–35 years, with an income for one family member up to 700 PLN.

In the literature, there are reports that miscarriage causes deterioration of the mental condition of women. The presented study made it possible to identify socio-demographic risk factors of an increased level of stress.

Objective:

The aim of the study was to determine the correlation between socio-demographic factors and the intensity of perceived stress inae group of women who were hospitalized due to miscarriage.

Material and methods:

321 women aged 18–35 years hospitalized due to miscarriage took part in the study. The diagnostic survey method – the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10) and the author›s questionnaire were used.

Results:

Age determined the intensity of stress, which was greater in the group of women aged up to 25 years than in the group of older women. Place of residence, education and financial situation did not determine the level of subjectively perceived stress in the group of women hospitalized due to miscarriage. Income determined the intensity of stress, which was the highest in the group of women with an income of up to 700 PLN per person in the family. The occurrence of miscarriages did not determine the level of subjectively perceived stress.

Conclusions:

There is a correlation between sociodemographic factors and the intensity of perceived stress in the group of women who were hospitalized due to miscarriage. The assessment of the correlation between sociodemographic factors and the intensity of perceived stress made it possible to distinguish a group of women at increased risk of developing an increased level of stress, which includes women: up to 25 years of age and in the age range 31–35 years, with an income for one family member up to 700 PLN.

REFERENCES (54)

1.

Ślusarska B, Nowicki G, Jędrzejewicz D. Poziom odczuwanego stresu i czynniki stresogenne na stanowisku pracy ratownika medycznego. Pielęgniarstwo XXI wieku 2014; 1(46): 11-18.

2.

Olesen ML, Graungaard AH, Husted GR. Deciding treatment for miscarriage-experiences of women and healthcare professionals. Scan J Caring Sci. 2015; 29 (2): 386-394.

3.

Pietropolli A, Bruno V, Ticconi C. Uterine blood flow indices, antinuclear autoantibodies and unexplained recurrent miscarriage. Obst Gynecol Sci. 2015; 58(6): 453-460.

4.

Nynas J, Narang P, Kolikonda MK, Lippmann S. Depression and Anxiety Following Early Pregnancy Loss: Recommendations for Primary Care Providers. Prim Care Companion CNS Disorders 2015; 17(1): 1-6.

5.

Ojule JD, Ogu RN. Miscarriage and Maternal Health. In Complications of Pregnancy. Intech Open 2019: 14-16.

6.

San Lazaro Campillo I, Meaney S, McNamara K, O'Donoghue K. Psychological and support interventions to reduce levels of stress, anxiety or depression on women's subsequent pregnancy with a history of miscarriage: an empty systematic review. Br Med J Open 2017; 7(9): 6-9.

7.

Volgsten H, Jansson C, Svanberg AS, Darj E, Stavreus-Evers A. Longitudinal study of emotional experiences, grief and depressive symptoms in women and men after miscarriage. Midwifery 2018; 64: 23-28.

8.

Miller SC. The Moral Meanings of Miscarriage. J Soc Philosophy 2015; 46 (1): 141-157.

9.

Quenby S, Gallos ID, Dhillon-Smith RK, Podesek M, Stephenson MD, Fisher J et al. Miscarriage matters: the epidemiological, physical, psychological, and economic costs of early pregnancy loss. The Lancet 2021; 397: 1658-1667.

10.

Napiórkowska-Orkisz M, Olszewska J. Rola personelu medycznego we wsparciu psychicznym kobiety i jej rodziny po przebytym poronieniu. Pielęgniarstwo Pol. 2017; 3(65): 529-536.

11.

Djidonou A, Tchegnonsi FT, Ahouandjinou CC, Ebo BH, Bokossa CM, Degla J, Fiossi-Kpadonou É. Prevalence and Factors Associated with Anxiety and Depression in Expectant Mothers at Parakou in 2018. Open J Psychiatry 2019; 9: 235-247.

12.

Chrzan-Dętkoś M, Walczak-Kozłowska T. Antenatal and postnatal depression – Are Polish midwives really ready for them? Midwifery 2020; 8: 9-11.

13.

Huffman CS, Schwartz AT, Swanson KM. Couples and Miscarriage: The Influence of Gender and Reproductive Factors on the Impact of Miscarriage. Women' s Health Issues 2015; 25(5): 570-578.

14.

Dembińska A, Wichary E. Wybrane psychospołeczne korelaty lęku przedporodowego – znaczenie dla praktyki położniczej. Selected psycho-social correlates of antenatal anxiety – and their signify cancer for obstetrics care. Sztuka Leczenia 2016; 43(1): 43-54.

15.

Sikora K. Reakcje kobiet po stracie ciąży oraz zachowania ich partnerów. Ginekol Położnictwo 2014; 9(3): 40-55.

16.

Ilska M, Przybyła-Basista H. Measurement of women’s prenatal attitudes towards maternity and pregnancy and analysis of their predictors. Health Psychol Rep. 2014; 2(3): 176-188.

17.

ESHRE-European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology: Special Interest Group for Early Pregnancy RCOG-Green Top Guideline 2006: 25.

18.

Chrzan-Dętkoś M, Kalita L. Rola wczesnej interwencji psychologicznej w profilaktyce i terapii depresji poporodowej. Psychoterapia 2019; 1(188): 47–61.

19.

Amirchaghmaghi E, Rezaei A, Aflatoonian R. Gene Expression Analysis of VEGF and Its Receptors and Assessment of Its Serum Level in Unexplained Recurrent Spontaneous Abortion. Cell J Winter 2015; 16(4): 583-545.

20.

Sariibrahim Astepe B, Bosgelmez S. Antenatal Depression and anxiety among women with Threatened Abortion: a CaseControl Study. Gynecol Obst Reproductive Med. 2019; 25: 17.

21.

Mutiso, SK, Murage, A, Mwaniki, AM. Factors associated with a positive depression screen after a miscarriage. BMC Psychiatry 2019; 19: 8.

22.

Duval R, Javanbakht A, Liberzon I. Neural circuits in anxiety and stress disorders: a focused review. Ther Clin Risk Management 2015; 11: 115-126.

23.

Betts KS, Williams GM, Najman JM, Alati R. Maternal depressive, anxious, and stress symptoms during pregnancy predict internalizing problems in adolescence. Depress Anxiety. 2014; 31(1): 9-18.

24.

Likis EF, Sathe NA, Carnahan R, Mc Pheeters MA. Systematic review of validated. methods to capture stillbirth and spontaneous abortion using administrative or claims data. Vaccine 2013; 31: 74-82.

25.

Robinson E. Pregnancy loss. Best Practice Res Clin Obst Gynecol. 2014; 28: 169-178.

26.

Cannella BL, Yarcheski, A, Mahon, NE. Meta-Analyses of Predictors of Health Practices in Pregnant Women. West J Nurs Res. 2018; 40(3): 425–446.

27.

Rymaszewska J, Szcześniak D, Cubała WJ, Gałecki P, Rybakowski J, Samochowiec J, Szulc A, Dudek D: Rekomendacje Polskiego Towarzystwa Psychiatrycznego dotyczące leczenia zaburzeń afektywnych u kobiet w wieku rozrodczym. Część III: Postępowanie w wypadku utraty ciąży oraz niepowodzeń w leczeniu niepłodności metodą in vitro. Psychiatria Pol. 2019; 53(2): 277–292.

28.

Borhart J, Bavolek R. Obstetric and Gynecologic Emergencies, An Issue of Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America. Elsevier Health Sci. 2019.

29.

Dunkel SC, Tanner L. Anxiety, depression and stress in pregnancy: implications for mothers, children, research, and practice. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2012; 25(2): 141-148.

30.

Mroczkowska D. Jakość życia kobiet po poronieniu ciąży. Życie i Płodność 2011; 4: 77-88.

31.

Płoch K, Dziedzic M, Matuszyk D, Frączek E. Czynniki sprzyjające utrzymaniu ciąży wśród kobiet hospitalizowanych z powodu zagrażającego poronienia. Pielęgniarstwo XXI wieku 2015; 4(53): 69-74.

32.

Murlikiewicz M, Sieroszewski P. Poziom depresji, lęku i objawów zaburzenia po stresie pourazowym w następstwie poronienia samoistnego. Perinatologia, Neonatologia i Ginekologia 2013; 6(2): 93-98.

33.

Engelhard IM, Hout MA, Schouten EG. Neuroticism and low educational level predict the risk of posttraumatic stress disorder in woman after miscarriage or stillbirth. Gen Hospital Psychiatry 2006; 28: 417-424.

34.

Daugirdaité V, van den Akker O, Purewal S. Posttraumatic Stress and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder after Termination of Pregnancy and Reproductive Loss: A Systematic Review. J Pregnancy. 2015: 1-14.

36.

Blackmore ER, Côté-Arsenault D, Tang W, Glover V, Evans J, Golding J, O'Connor TG. Previous prenatal loss as a predictor of perinatal depression and anxiety. Br J Psychiatry. 2011; 198(5): 373-378.

38.

Nakano Y, Akechi T, Furukawa TA, Sugiura-Ogasawara M. Cognitive behavior therapy for psychological distress in patients with recurrent miscarriage. Psychol Res Behav Management 2013; 6: 37-43.

39.

Kong GWS, Lok IH, Yiu AK, Hui ASY, Lai BPY, Cheung TKH. Clinical and psychological impact after surgical, medical or expectant management of first-trimester miscarriage - a randomized controlled trial. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynecol, 2013; 53(2): 170-177.

40.

Treppesch KI, Beyer R, Geissner E, Rauchfuß M. Backdating miscarriages and abortions in patients at practice-based gynecological offices: Worth a question? Woman Psychosom Gynecol Obstet. 2015; 1-2: 9-15.

41.

Bowles SV, Bernard RS, Epperly T, Woodward S, Ginzburg K, Folen R, Perez T, Koopman C. Traumatic stress disorders following first-trimester spontaneous abortion. J Family Pract. 2006; 55(11): 969-973.

42.

Cheung C, Chan C, Ng E. Stress and anxiety depression levels following first-trimester miscarriage: a comparison between women who conceived naturally and woman who conceived with assisted reproduction. Int J Obstet Gynecol. 2013; 120: 1090-1097.

43.

Bubiak A, Bartnicki J, Knihnicka-Mercik Z. Psychologiczne aspekty utraty dziecka w okresie prenatalnym. Zdr Publ. 2014; 4(1): 69-78.

44.

Sikora K. Reakcje kobiet po stracie ciąży oraz zachowania ich partnerów. Ginekologia i Położnictwo 2014; 9(3): 40-55.

45.

Toffol E, Koponen P, Partonen T. Miscarriage and mental health: Results of two population-based studies. Psychiatry Res. 2013; 205: 151-158.

46.

Kersting A, Wagner B. Complicated grief after perinatal loss. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2012; 14(7): 187-194.

47.

Holka-Pokorska J, Jarema M, Wichniak A. Kliniczne uwarunkowania zaburzeń psychicznych występujących w przebiegu terapii niepłodności. Psychiatria Pol. 2015; 49(5): 965-982.

48.

Dugiel G, Tustanowska B, Kęcka K, Jasińska M. Przegląd teorii stresu, Acta Scientifica Academiae Ostroviensis, Sectio B, Nauki Medyczne, Kultura Fizyczna i Zdrowie 2012; 47-70.

49.

Blackmore ER, Côté-Arsenault D, Tang W, Glover V, Evans J, Golding J, O'Connor TG. Previous prenatal loss as a predictor of perinatal depression and anxiety. Br J Psychiatry. 2011; 198(5): 373–37.

50.

Sygit-Kowalkowska E. Radzenie sobie ze stresem jako zachowanie zdrowotne człowieka perspektywa psychologiczna. Hygea Public Health 2014; 49(2): 202-208.

51.

Borhart J, Bavolek R. Obstetric and Gynecologic Emergencies, An Issue of Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America. Elsevier Health Science 2019.

52.

Adib-Rad H, Basirat Z, Faramarzi M, Mostafazadeh A, Bijani A. Psychological distress in women with recurrent spontaneous abortion: a case-control study. Turk J Obstet Gynecol. 2019; 16(3): 151-157.

53.

Guzewicz M. Psychologiczne i społeczne konsekwencje utraty dziecka po poronieniu. Civitas et Lex 2014; 1: 15-27.

54.

Ockhuijsen HDL, Hoogen A, Boivin J, Macklon NS, Boer F. Pregnancy After Miscarriage: Balancing Between Loss of Control and Searching for Control. Resn Nurs Health. 2014; 37: 267-275.

Share

RELATED ARTICLE

We process personal data collected when visiting the website. The function of obtaining information about users and their behavior is carried out by voluntarily entered information in forms and saving cookies in end devices. Data, including cookies, are used to provide services, improve the user experience and to analyze the traffic in accordance with the Privacy policy. Data are also collected and processed by Google Analytics tool (more).

You can change cookies settings in your browser. Restricted use of cookies in the browser configuration may affect some functionalities of the website.

You can change cookies settings in your browser. Restricted use of cookies in the browser configuration may affect some functionalities of the website.